Why ‘build, baby, build’ must go beyond planning reform

Bradshaw's Matt Brighty has taken a closer look at the UK’s construction performance challenge.

Major construction programmes are being undertaken on an unprecedented scale globally, with the number of megaprojects underway up 280% over the past 15 years. The UK is part of this surge with around 500 projects in progress, and the government, under a push to “build, baby, build”, boasts to have approved 21 major infrastructure projects in its first year.

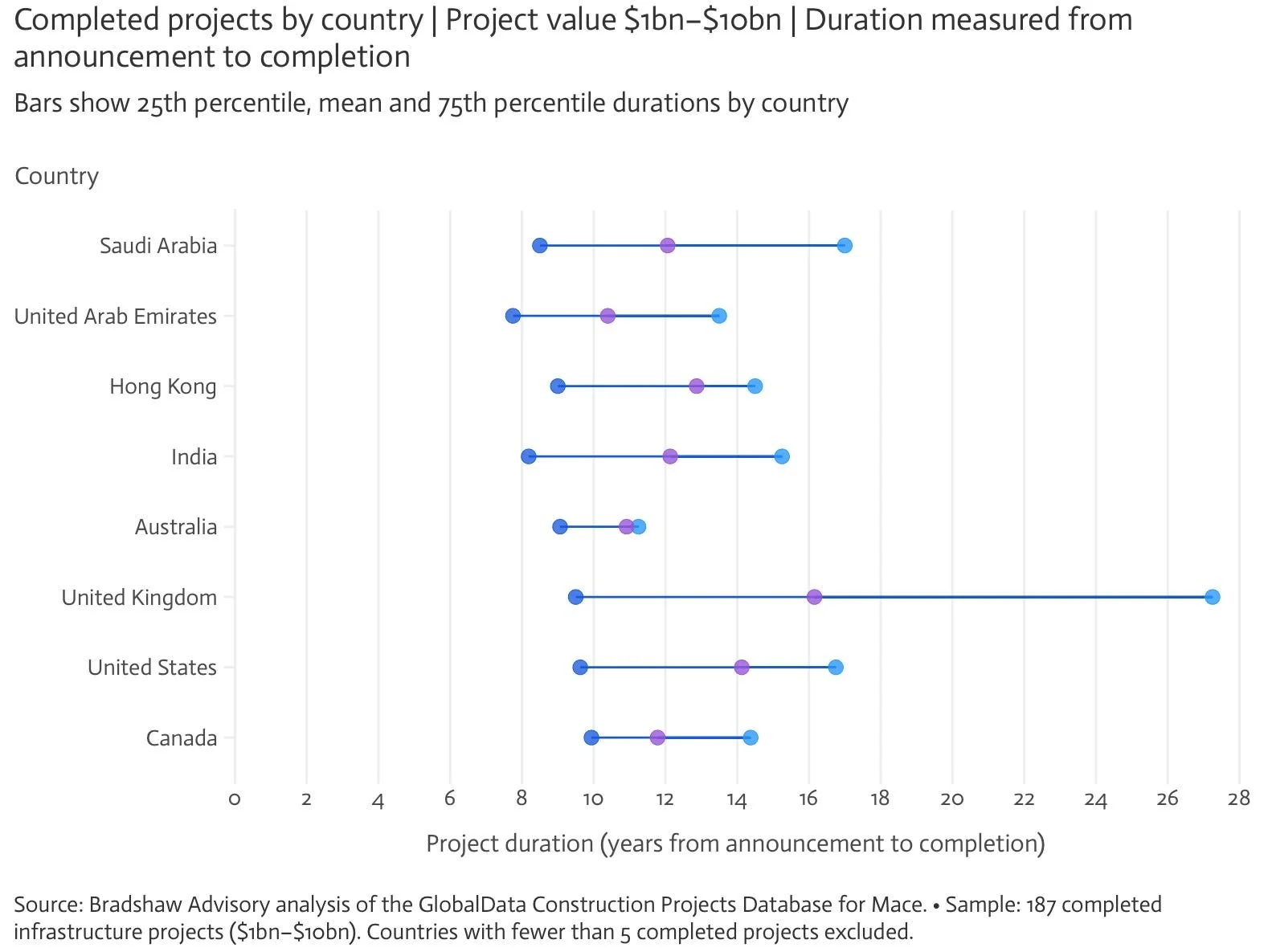

The government acknowledges that its delivery record is weak - UK infrastructure projects take 16.2 years on average, some 25% longer than elsewhere - and are aiming to close this gap by tackling blockers such as planning delays, regulatory bottlenecks and a lack of strategic direction. But these fixes stop short of the more fundamental constraint: stagnant construction productivity.

Building blockers

Planning reform was identified as a key priority for Labour well before the general election - and for good reason. The average time to secure consent has doubled since 2009, with projects now routinely caught in a web of messy statutory processes, opaque responsibilities and legal risk aversion. Planning is seen as a big barrier to building in Britain, and the Planning and Infrastructure Bill (PIB) is central to the government’s plans to deliver homes, clean power, hospitals and schools.

Even with the first iteration of the PIB still working its way through parliament, Rachel Reeves has instructed officials to draw up proposals for a second, this time aimed at accelerating delivery on “critical” national projects such as a third Heathrow runway. Ministers are also tackling gridlock in the Building Safety Regulator (BSR), where approvals run far beyond targets. The average time it takes to get approval at gateway 2 is 36 weeks - the BSR’s target is 12. Like with planning, reforms here aim to accelerate decisions and unlock delivery.

Another drag on progress has been the lack of a clear strategic direction. The government’s Infrastructure Strategy, complete with an updated 10-year project pipeline, is intended to fix this by providing a long-term, transparent framework that sets priorities, signals funding commitments and gives industry and investors greater certainty.

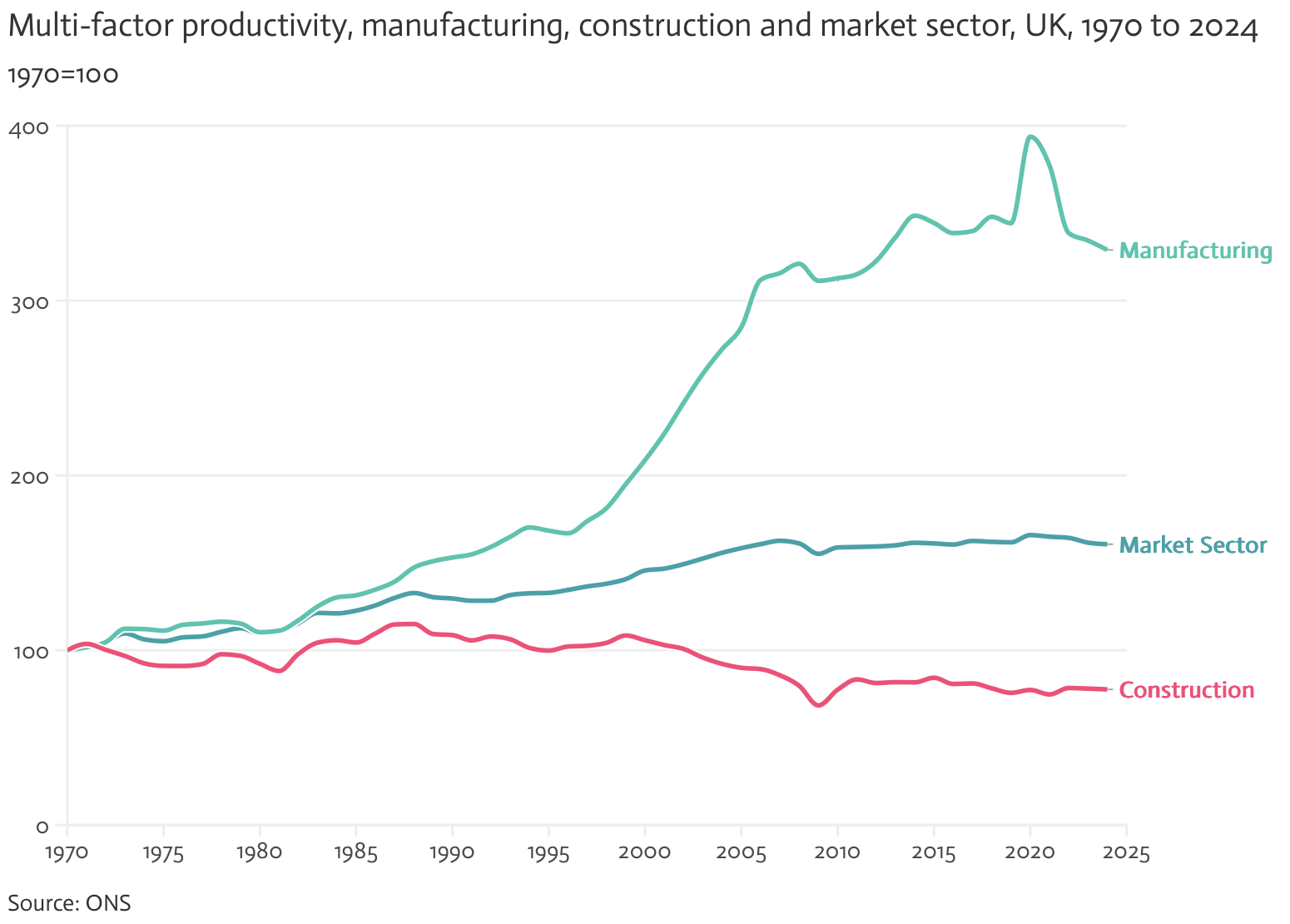

However, while planning blockers and strategic uncertainty are being resolved, productivity remains untouched. Construction productivity has been stagnant for decades, lagging well behind the wider economy, yet it consistently falls outside the scope of reform efforts. Bureaucratic streamlining may ease some of the UK’s distinct underperformance, but only scratches the surface of a far larger global productivity problem where the real gains lie.

With few exceptions, construction productivity is an issue everywhere - rising just 0.4% annually (global aggregate, output-weighted) between 2000 and 2022 compared with 2% for the wider economy. This international drag cannot explain the UK’s specific failings - UK infrastructure projects taking 25% longer than average - but it does set a ceiling. Unless productivity improves, the gains from planning reform or regulatory streamlining will be capped.

Some countries, particularly in Asia-Pacific, have achieved far greater productivity growth. For example between 2000 and 2021, construction productivity in China grew at a compound annual rate of 4%, compared with a global average of 1% (global country average, unweighted). This shows that the trap is not inevitable and offers the UK potential routes out. They have embraced digitalisation, modular construction and new delivery models to drive faster, more efficient outcomes.

Productivity progressors

For example, Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) introduce innovative techniques, such as offsite manufacturing, prefabrication and the use of advanced materials, in an attempt to improve efficiency, quality and sustainability. The UK government has been an advocate for MMC in recent years with their Construction Playbook setting a presumption in favour of offsite manufacturing and requiring departments to set targets for its use in public contracts. MMC has also been strongly encouraged in every major review of the construction industry, from Latham and Egan through to Farmer.

Despite this, MMC uptake remains low, and far from standard practice, held back by things like high upfront costs, uncertain returns, skills and digital capacity gaps, and ongoing concerns over fire safety and accreditation.

The construction industry retains a reputation for technological conservatism, even as manufacturing and logistics have been transformed by automation and digital integration. The potential of tools like Building Information Modelling (BIM), digital twins, drones, robotics and real-time project management platforms is widely acknowledged, yet adoption remains patchy in a sector that is fragmented, under constant cost and time pressure, and invests far less in R&D than comparable industries.

The government must take a more active role in driving innovation uptake in construction. This means:

Providing targeted support to de-risk investment in offsite factory capacity, construction equipment and supporting technologies

Creating skills programmes, including government-backed training in areas like modular design, prefabrication and BIM to ensure the workforce can operate, manage and maintain these systems

Establishing a single national accreditation system for MMC, replacing fragmented schemes with uniform safety and quality standards recognised by lenders, insurers and procurers

Standardising data sharing, reporting and benchmarking, modelled on proven approaches such as the Project Data Analytics Taskforce proposals, providing a clear view of productivity drivers

Amending procurement and appraisal frameworks to more generously rewards innovative suppliers and embed the environmental and social benefits they bring into decision making

Crucially, uptake also depends on the contracting models and organisational cultures in which innovations are to be deployed. Traditional, lowest price, project-by-project models lead to chronically low margins, fragmented supply chains and adversarial relationships that disincentivise innovation and discourage long-term investment. More collaborative models can lower barriers to innovation. For example, giving investors greater certainty over ROI creates stronger incentives to back new approaches that can raise productivity.

Constructing collaboration

UK construction has begun to shift away from adversarial contracting. Contracts are introducing more collaborative features, but their scope remains limited and change is incremental. Deeper models - Alliancing, Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) and frameworks such as Project 13 - go further by integrating clients, contractors and designers into a single team from the outset. Examples like the Northern Line Extension, Anglian Water @One Alliance and the Smart Motorways Programme show that when risks and rewards are shared, decisions are made in the best interests of the project. These models have been proven to outperform traditional procurement models on cost, schedule and quality. Importantly, they also create the market conditions for innovations to take root.

However, change is driven by clients, and clients, wary of insolvencies and fragile supply chains, try to avoid extra risk. RLB’s 2025 survey shows some shift towards more collaborative procurement, with 40% of contractors reporting an increase in collaborative practices, but momentum is slowing as the rate of increase in client risk appetite has fallen from 35% to 25%. Further change will depend on clients being able to see clear benefits. Without this, clients revert to adversarial, price-driven models.

If the government wants infrastructure delivered faster, at scale and with lower risk, it must also aim to accelerate adoption of collaborative procurement. As the sector’s largest client, the government is uniquely positioned to set the tone for the whole industry.

Policy initiatives like the Construction Playbook provide the direction but it remains unevenly applied. Its ‘comply or explain’ approach should, at the very least, be underpinned by a rigorous justification threshold to prevent default to traditional methods, and the Institute of Civil Engineers recommends that the Playbook be mandated on a ‘comply’ only basis to ensure consistent application across government projects.

Build, baby, build

If the government wants projects delivered on time, on budget and at scale, it must change how we build. That means backing innovation through funding, skills and forward-looking frameworks; embedding data discipline with transparent reporting; and promoting collaborative procurement that creates the conditions for productivity gains.

With these reforms, Britain can deliver faster and at lower risk, unlocking far greater gains than planning and strategy reform alone.